Instagram is a monster that eats your emotions

Instagram is a monster that feeds on your emotions, it is a marketplace that runs on your data. It is not a tool for political change, and worse than that, it is pushing us against each other because the most salient content it needs is extreme content. On Instagram, we are data points that scream into the void of the advertising pipelines of Meta (formerly known as Facebook).

First, why am I writing this? Because I am afraid my generation suffers from the illusion that doing very simple actions like tapping on a glass screen to upload photos on a privately-owned social network will create a snowball effect of political change, and if they don't do that, they feel guilty, and their mental health deteriorates. They feel personally responsible for the ills that rot the world. Political change is possible but I firmly believe it is about sustained collective action in the real world, and not individual digital action. Most people say they "don't care about politics" yet hope for the better. We need to change that.

Instagram is a privately-owned social network that makes money the more you consume and interact with it. Most of the time, we are aware of this. We see it for what it is, a tool to fry your brain on senseless content (doomscrolling and brain rot). A place of comparison where we are communicating with people who we know (if we have less than thousands and thousands of followers) to position ourselves in the social group. But some dissonance causes us to think that we can sometimes "be serious" on Instagram. It is owned by Meta (formerly known as Facebook), which Mark Zuckerberg owns the voting rights of. The content is irrelevant as long as the engagement metrics are here: time spent using, number of interactions, etc. Every single thing you do, from how many times you watch a reel, the number of taps you make, how long you look at someone's story is recorded. Petabytes of data are created hourly to improve the machine. Smarter people than you and me spend their days optimizing for these. It is designed for engagement above all else, and such a system, even downstream, cannot be seen as a tool for political change. It is controlled and designed for other things.

At first however, some social networks were designed to foster connection and exchange between people, that was back in 2007-2012. Then, the ad business model made Facebook a real threat to Google because it was growing so much. They bought Instagram and WhatsApp, and now control the tools with which we communicate. The tools of communication must be seized! (if we want political change from them).

I am worried the mechanics are as follows: we see something disturbing, we post about it thinking it needs to be shared widely, we feel slightly relieved by doing "a little thing which is better than nothing", we get some biological release of feeling good, we see other people doing the same anyway. We get angry at others who don't do the same. This is because Instagram is about mimetic behavior. Instagram is about comparing ourselves to others, and that's it. It was built by people who thought the design paradigm of the "news feed" was "an empty vessel for the mind". It pits us against each other on a digital arena. Isn't it weird that we “know” for a fact that when people share stories they are curating their lives, but when we are sharing political content, we suddenly are "serious". It is the same thing. Because the medium is the message.

The theoretical framework underpinning social media is now well-known. Mimetic behavior is at the core of the design principles of these platforms. Mimetic desire, a theory by René Girard is an idea that both Zuckerberg and Peter Thiel (one of Facebook's first investors) deeply believe in. Is postulates that there is no original desire. We copy the desire of others we believe as more legitimate or higher status, that it's all about the social group. The same goes for behavior. This creates comparison and competition and favors social tensions (the infamous polarization problem that plagues American society, and that will plague other Western societies that import their culture from the United States, such as France).

I have seen the best minds of my generation I know share information they thought was truthful but it was made by satirical accounts. I have seen competition and insults among the Lebanese because some were "posting" about Palestine, and others were not. I have seen stories with dead children then some about partying, then dead children again, asking me to watch or else I'm a bad person. Because Instagram does not require you to think about how others view your content, it incentivizes you to post no matter what, resulting in these absurd Story viewing experiences.

"Raising awareness" has been used over and over as an outcome of social media posting, but I have not seen any significant political change because of it, especially when it comes to international politics (and not societal issues, more on that below).

What does raising awareness mean, and how is it more helpful to the people we are raising awareness for, than the people doing this work? Raising awareness, without measuring impact, which is what most people do, is done because of social signaling. The same people who were criticizing Hezbollah for dragging Lebanon into war are the ones who celebrated some of its victories later — we play these games to position ourselves in the social group. The high Lebanese society is a quintessential example of this.

Instagram makes us believe that "every little helps", but "it don't". We can raise money, and raise awareness with it, so that's not nothing, but we cannot create lasting political change. What changed in Lebanon after 2019 and everyone changed their profile picture to little red circles? What changed after everyone posted a black square in June 2020? What changed in Rafah after all eyes were set to it?

We have raised awareness so much that people have become numb to the awareness. The human mind adapts to the darkest shit, observe your own acceptance of extremely bad situations that you personally lived. Repeated exposure dilutes resistance. This is learned helplessness and we all suffer it in different degrees.

Political change happens in the real world via collective action. Political change happens when the laws or the people who make the laws are changed. Political change happens when we get involved in politics and we don't say "I don't care about politics". Political change may require out of bounds action in order to move the current people responsible away. Have we fallen so much that we believe that we can move the equilibrium by stroking the small lamp that is your phone?

During the French revolution, people who were less than 25 fought and died to change the system. Did you think the king wanted to leave?

My core point is that political change is possible via real-world collective action, and not the aggregation of individual social media activism. Indeed, the group in the real-world is more than the sum of the parts, where it is merely an aggregate here.

Societal causes are different than geopolitical ones.Social media has brought changes in gender relationships, because the problematic actors (men) are much more reachable here than the actors of geopolitical action. Slowly, shame is changing camps, and men are starting to realize they need to treat women with respect. The reachability of the problematic actors is the core difference between geopolitical and societal issues, and the effectiveness of Instagram for change.

I am not morally better than you dear reader, nor am I a paragon of political involvement. But just like anyone else in these dark digital pits, I express myself.

I urge my soon-to-be former friends and soon-to-be enemies not to feel guilty for not posting about the destruction of the world. It will not change anything, you do not have to do it, you do not have to contribute here. If you want to get involved, either change the law or change the people writing the laws, or put your physical integrity at risk, if you so desire. But peeing in the ocean is not worth your mental health because alone you are powerless.

Instagram is not an instrument for political change. It is where you watch your friends post for social motives, whether they accept it or not, and myself freely admitting to it. It is the virtual schoolyard from high school, it is not the public town square where your powers of Athenian discourse generate the desire to change the world. Because it is made to make just YOU feel certain ways: entertained, sad, excited, angry, etc. So you consume further with it. It is a monster that you feed with your emotions.

Why speed matters for early stage companies

A simple intuition is that it is about course-correcting.

Velocity mitigates the mistakes in positioning, especially early on. You don't have to be fast. It's just that a team that executes faster will mechanically be able to “try again” more times than a slower one.

How I use LLMs for work and life (Spring 2025)

I thought I'd write a short post for future reference.

This is how I use LLMs daily for different tasks, such as:

- Writing a message to a specific audience while taking into account a message history or context (I use Claude Projects for that)

- Generate ideas to solve a problem—although I try to do that less often to limit my resistance to thinking, which is alarmingly increasing

- Analyze data (PDFs, spreadsheets)

- Help me identify reasoning or logical fallacies in my writing

- Learn about new concepts

- Investigate trends

- Answer cooking and household questions

- Analyze personal health data (privacy hazard, of course)

- Provide high-level legal advice

- Perform comprehensive search for a given subject, etc.

I mostly use o3 and Claude 3.7 Sonnet (Extended Thinking).

Some heuristics:

- Keep conversations below 200k tokens (about 50k words). I don't believe in this 1M token thing (I may be irrational)

- Edit an already sent message instead of trying to tell the AI to correct itself if its response was bad. So let’s say I ask it a question about solar power engineering… it answers in an academic way but I wanted a business approach… instead of sending a new message saying “i want this to be about business”, I edit the first message I sent to steer the AI (less tokens burnt per day, and answers better, as any noise in the context window will prevent optimal behavior)

- Improve prompts when asking about mission critical stuff (assumption: humans don’t know how to prompt). I use the Anthropic Console for that or I use speech-to-text. I noticed that longer prompts are better and it's easier to speak than type

- Be diligent about Project context (as little noise as possible, delete old files, clean up regularly)

René Girard on US-China

His thoughts on international relations come in his final book, Battling to the End (2009), a commentary on the military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, written as a dialogue with the literary critic Benoît Chantre. There, Girard describes geopolitical conflict as the result of mimetic desire: “Everyone now knows that the looming conflict between the US and China, for example, has nothing to do with a ‘clash of civilisations’, despite what some might try to tell us. We always try to see differences where in fact there are none. In fact, the dispute is between two forms of capitalism that are becoming more and more similar,” Girard wrote. He understood the trade war as the result of similarity rather than difference and believed it could lead to a conflict that would wipe out the world. He called it the apocalypse.

It is not too far fetched to view the US as become more illiberal and China turning towards finance and technology.

The Most Valuable Commodity in the World is Friction

I think what we're witnessing isn't just an extension of the attention economy but something new - the simulation economy. It's not just about keeping you glued to the screen anymore. It's about convincing you that any sort of real-world effort is unnecessary, that friction itself is obsolete3. The simulation doesn't just occupy your attention, right, instead it replaces the very notion that engagement should require effort. Which is… wild.

How software mediates thought and constrains free will

There is a fundamental difference between modes of composition: dictation, pen on paper, or keyboard. These differences noticeably influence the final output, although the effects remain unpredictable, emerging downstream from the complex system of communication.

Sometimes I'm overly aware of the chosen mode and find myself asking: what would the output—and thus the communicated message—have been if a different mode had been selected? What would Socrates' ideas have become without Plato’s writing? How would Kant’s thoughts differ had he used a keyboard? And what if Aaron Swartz had relied on pen and paper?

Even when expressing the exact same idea—if such a thing is possible—the resulting outputs might differ so profoundly that the behavioral outcomes become even more unpredictable. Different modes of composition inherently create different outcomes, influencing the subject’s possibility of self-determination in digital environments.

✴✴✴

Digital composition is uniquely distinct because its interfaces are intentionally designed. They embed someone else's mental model of creativity and thus limit possibilities, exerting a constituting power of creating contingent “reality” and possibilities—or presenting composition merely as one option among many decided by the designer.

Physical tools (paintbrush, pen), by contrast, have constraints arising from material reality rather than another person's mental model, fostering a distinctly different relationship to free will.

Marxist inversion: software is marketed as “tools”—the greatest farce—yet they lack the essential nature of true tools, which inherently offer maximal free will within their physical constraints.

The homogenization of writing technology (keyboards, word processors) may consequently limit the emergence of novel philosophical ideas. Modern UIs function as non-neutral mediators of thought—an invisible architecture shaping our thinking beneath our conscious awareness.

Perhaps this is why we cannot yet adequately theorize social media. Understanding the influence of "tool software" on composition, communication, and free will is a prerequisite to unraveling deeper “social software” aspects: feedback loops between composition and response, algorithmic effects, and the creation of new social norms.

Un hiver à Londres

Je marche seul dans l'hiver de Londres vers un restaurant de pizza, aussi appelé pizzeria. Cette franchise promet des pizzas napolitaines authentiques. Voici donc un terme qui a été vidé de son sens dans l'espoir d'augmenter ses marges.

Je rentre et je découvre un lieu très bien éclairé avec peu de clients. Il est 19h et la nuit est déjà complète. On m'installe, et je prétends regarder le menu que j'ai déjà lu sur Internet. Je commande une salade de roquette, une pizza à la n'duja et un negroni. Avant de pouvoir passer commande, j'ai attendu assez longtemps en regardant avec nonchalance les serveuses et serveurs discuter avec les pizzaiolos dans un italien qui me semblait, lui, tout à fait authentique. L'impatience pointait son nez.

Un couple vint s'installer à côté de moi. Je remarque qu'ils ne sont pas encore un couple. Ils essayent de se séduire. Ils promettent de ne pas boire de bière ce soir. Lentement, je descends mon negroni. Le serveur les informe : il n'y a plus de pâte sans gluten ce soir. Ils se lèvent et s'en vont. Je termine mon verre. Je demande une pinte et termine ma pizza. Vint s'assoir un nouveau “couple”. Deux individus hétérosexuels qui alternent les platitudes afin d'évaluer leur compatibilité. Elle a mangé trop de fromage en Suisse. Elle commence à faire la liste des différents pays qu'elle a visité en Europe. Il fait des compliments maladroits.

Elle, américaine, lui suggère qu'il a plus voyagé qu'elle au sein des États-Unis. Il est terne mais elle continue. Elle dit qu'elle n'a pas envie de retourner au Portugal où elle a été avec sa mère. Ils sont tous les deux allés en Croatie. Il intime que de son côté, c'était pour un “week-end”. Elle propose qu'ils s'évadent un weekend ensemble, ce à quoi il ne répond pas directement.

Le tiramisu est moyen et trop chocolaté. Elle mentionne son besoin de se coucher à 23h. Il ne réagit pas chaudement. Il dit qu'il aimerait vivre à Paris, elle lui dit “you're so funny”.

Tout du long, les hauts-parleurs laissaient échapper de grésillants tubes rock désuets et fades.

Nvidia's CEO defends his moat as AI labs change how they improve their AI models

“Foundation model pretraining scaling is intact and it’s continuing,” said Huang on Wednesday. “As you know, this is an empirical law, not a fundamental physical law, but the evidence is that it continues to scale. What we’re learning, however, is that it’s not enough.”

That's also what I would say, if the growth of my business depended on people buying my chips, which are the gold standard for pre-training.

Source: TechCrunch

Chienne de vie

Chienne de vie. Il n’y a pas de saison pour se sentir comme un mégot écrasé entre les gros doigts poisseux du Hasard. Et pourtant. Aucun regard, aucun amour, aucune civilisation ne résiste aux immenses roues du Temps. Il aplatit tout Passé et forme un horizon laid sur lequel nos yeux se fixent malgré nous. Est-ce ça l’enfer ? Une plage longue et lisse faite de vide dans laquelle la seule chose à voir est ce laid horizon. Ça ne peut pas être ça. Il existe malgré tout des lueurs qui frémissent. Dans ces abris temporaires creusés par la lumière se trouve un répit qui accueille. Trouver les lueurs et y courir.

Mais c’est vrai, il n’y a pas de soleil caché derrière les nuages. C’est à nous de trouver l’eau dans ce désert même quand ces lueurs semblent être des mirages. Inscrire sur le sable de cette plage vide nos vœux avec ferveur, ce que l’on souhaite voir exister pendant cette chienne de vie. On peut faire beaucoup, on le doit certainement. Entendre la réalité de l’autre, l’épauler et le surprendre quand la tempête gronde. Cette chance que l’on crée pour autrui par notre présence ne garantit aucun changement, aucun succès. On échoue trop souvent. Mais c’est bien dans ces mouvements répétés, en tendant sa main encore et encore, que l’on trouve la force de regarder l’Absurde, pas comme un adversaire, mais comme une drôle d’étoile qui nous guide sans nous éclairer. Un compagnon indéniable qui prend souvent sans rendre. Oui, il reste beaucoup à faire pour marcher cette route sans se tourner vers la plage vide et lisse de l’enfer, ni vers l’horizon laid du Passé aplati par le Temps. Encore beaucoup !

Wittgenstein's word games, or how to communicate (a bit) better

Wittgenstein, the philosopher of language, may give us clues for better communication and self-understanding.

In ancient Greece, words like "justice" and "knowledge" were used without hesitation, conveyed through examples. There were no definitions proper. Socrates came along and asked, "What is justice? What is knowledge?" He thought words correspond to things. Examples capture only partial information about a word. This is his "name" theory of language.

Socrates sought definitions for all instances of a word. Wittgenstein, however, saw Socratic dialogues as a "frightful waste of time," proving nothing.

Wittgenstein proposed "family resemblances" between instances of a word's use, like traits shared among family members. Consider "game": board games, ball games, video games... no single commonality, but overlapping similarities and affinities. They are all "games". There might be a definition that encapsulate all but would need to be changed for any new "thing" that looks like a "game". Wittgenstein proposes to stop thinking... and to just look... for meaning of what is said.

A single word can form a family without one common essence. Seeking a single definition is nonsense. Definitions describe usage patterns! Not a word's true nature. Maybe this is why poets help us see new light on known words. And unlike Socrates proposed, word don't correspond to things.

Language can make us prey to unsound assumptions. How many misunderstood messages? Too many but it's just life. One solution is perspective: seeing words as tools for various uses/usage patterns, not labels attached to things. The meaning of "justice" depends on the activity at hand.

This applies to religion too. It is not about metaphysical claims, but a passionate commitment to living by a certain interpretation of life. Seen like this, religion resembles philosophy to some extent. Religious language expresses practical commitment, not factual/scientific belief. These language games are not necessarily in conflict.

Words are tools... we use to play "language games" in communication. Not by ill intent. But because words are complex and don't have a singular definition. Just as a court uses model cars to explain an accident, we paint mental pictures for others with our words

When a parent tells a scared child, "Don't worry everything is going to be fine," they aren't playing the Rational Prediction From Available Facts game, but rather the Words as an Instrument of Comfort and Security game. So is the colleague playing "Constructive Criticism" or "Office Politics"?

Failing to recognize the language game in front of us creates misunderstandings. It is harder than just "saying it". Even though everyone is better off when the talk is plain and straight. If your partner says, "You never help me. You're so unreliable," they may sound like they're playing the Stating the Facts game, but are playing the Seeking Reassurance game. Context is key.

Better communicators stay aware of identify language game being played. They can offer or ask for clarification of intent. They can stay flexible and not jump to conclusions based on singular words. They can accept ambiguity. Use meta-communication "I'm not sure how to say this but..."

What allowed Wittgenstein to adopt this radical view? A lifelong and overriding commitment to clarity and perspective as inherently valuable. Truth maybe matters less than clear sight - really seeing what's before us.

Again, don't think, look

Consequently, hosting a lavish banquet or ordering lobster is no longer a sufficient signifier of status; today, a sign of true wealth is the ability to forgo food entirely. Eating essentially betrays a person’s most basic human needs; in an era obsessed with ‘self-optimisation’, not eating suggests that a person is somehow ‘beyond’ needs and has achieved total mastery of their body with a heightened capacity for efficiency and focus.

What joy!

— Source

Mistral and culture

“The whole A.G.I. rhetoric is about creating God,” he said. “I don’t believe in God. I’m a strong atheist. So I don’t believe in A.G.I.”

A more imminent threat, he said, is the one posed by American A.I. giants to cultures around the globe.

“These models are producing content and shaping our cultural understanding of the world,” Mr. Mensch said. “And as it turns out, the values of France and the values of the United States differ in subtle but important ways.”

But this has been happening since the Second World War Mr. Mensch. And it's not stopping now, even though you realized it.

— NYT

Klarnas AI assistant, powered by @OpenAI, has in its first 4 weeks handled 2.3 m customer service chats and the data and insights are staggering: – Handles 2/3 rd of our customer service enquires – On par with humans on customer satisfaction – Higher accuracy leading to a 25% reduction in repeat inquiries – Customer resolves their errands in 2 min vs 11 min – Live 24/7 in over 23 markets, communicating in over 35 languages It performs the equivalent job of 700 full time agent

Oh yes, it’s happening. — Marginal Revolution

Amazon lets advertisers use generative AI to make product shots more lifelike

For advertisers without a graphic design or creative team, this is a quick solution to spruce up images that would otherwise be a bore

Complement this with auto-generated product descriptions, and Amazon might be one of the only Big Tech company making the most impactful “under the hood” AI improvements for their customers. That is, they are not making fancy bots or automatic PowerPoints and over-doing the “we're riding the AI wave” thing.

Also, to note:

Amazon says putting products in a lifestyle scene can lead to 40 percent higher click-through rates

How to Pour a Beer the Right Way

How do you pour a beer? You think you know the answer. You’re pouring the beer into a tilted glass, and minimizing the foam. According to Max Bakker, a Master Cicerone (or sommelier for beer), you’re getting it wrong. Above, he demonstrates the proper technique. Watch and learn.

The Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics

The Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics says that you can have a particle spinning clockwise and counterclockwise at the same time – until you look at it, at which point it definitely becomes one or the other. The theory claims that observing reality fundamentally changes it.

The Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics says that when you observe or interact with a problem in any way, you can be blamed for it. At the very least, you are to blame for not doing more. Even if you don’t make the problem worse, even if you make it slightly better, the ethical burden of the problem falls on you as soon as you observe it. In particular, if you interact with a problem and benefit from it, you are a complete monster. I don’t subscribe to this school of thought, but it seems pretty popular.

The Word Algorithm Originates in 9th Century Baghdad

The word algorithm comes from the name of a Persian mathematical genius, al-Khwarizmi, who dealt with mathematical sorcery in the 9th century. Although he did not invent algorithms in their contemporary sense i.e a finite sequence of rigorous instructions, he did inspire the Western world to use Arabic numerals instead of the clumsy Roman system. And he can be thanked for the word algebra.

It is when his works were translated into Latin and Italian that his name transformed into Algoritmi. And then his name entered the mainstream when it started to mean arithmetic in English.

It is striking to think that some people’s names became the semantic representation of an essential concept of science and technology. How often did that happen? — youtube.com

A Product Model to help PMs communicate clearly

I dream of a world where a Product Model can be generated from the organization of the backend files that respect the Domain-Driven Design (DDD) approach. That would quickly enable Product people to formalize a shared language from real code, and not spend hours philosophizing about why X should be named Y. Alas, this time has yet to come.

Indeed, one of the hard things to do in product development is to come up with a naming convention for your app that makes sense to everyone. Engineers, designers, and everyone else on the team need this shared language to talk about the product.

Another thing that is important for Product Managers is the ability to quickly conceptualize requirements for a feature or a product. Sometimes, user stories are too vague or incomplete.

Taking free inspiration from DDD, which states that in naming, the engineering logic must be as close as possible to the real-world, business logic, we can imagine the following model:

Domain Layer

This is where we name the entities and concepts that power the product. Domains are where the unique business logic is expressed. Say you are building an ecommerce app, you might have Cart, Accounts or Payments. If you're building an AI companion dating app, you might have Profile or Chat.

Infrastructure Layer

To me, this is where the backend orchestrates services that talk back and forth with the database. This is where I might refer to purely technical, non-visual elements such as a matching algorithm or a dedicated LLM logic.

Application Layer

This is the traditionally used layer when Product people think about products. This can capture interaction-based, user-centered flows that blend different objects from the Domain and Infrastructure layers, such as Sign Up or Add Item to Cart.

In short, because software applications are complex systems, thinking about the Application layer is not enough.

Product people should take into account the impact of a new feature in conceptual terms (Domains) and in technical, non-visual terms (Infrastructure).

Some Tips to Detect Fake News

Two things to keep in mind:

Remember the business model of media entities. Beneath the noble intention of sharing information, the business model of media companies is to maximize the number of people seeing ads on their properties, so they maximize traffic. How? Boring stuff doesn't drive traffic, but drama, and thus exaggeration, does.

Remember the goal of arguments, even online. A successful argument refutes the central thesis of the other party's argument. Beware of fallacies and biases like personal attacks (ad hominem), misrepresenting/exaggerating the opponent's argument to make it easier to attack (straw man fallacy), or saying that something is true because it's supported by an authority (appeal to authority). There are many more.

Without further ado, here are the tips:

- Check the source. A random Twitter/X account with 13 followers can share a post with 1M views. But it doesn't mean that the content is legit. Even accounts with a lot of followers are unreliable. One example is The Spectator Index (2.5M followers) which always exaggerates its claims for more views. Check the replies, check the origin of the information. Who shared it first? Yes, reputable sources are very hard to find. A heuristic I use is that if the content is sensationalistic and without context, there is a good chance that the “fact” is being exploited.

- Cross-check with other sources. If only one source shares the information, and you feel that they might not be a primary source, then exercise caution. One source is not enough to guarantee the validity of the information. Consider checking other sources.

- Check dates & times. A lot of people discard checking the date or time of content they share. Don't be like them! Check the date & time.

- Beware of emotional manipulation. Maybe I'm weird but my radar is triggered when the content shared is particularly dramatic (physical abuse, suffering children). Indeed, whenever we see suffering, our rational mind shuts off, and we are outraged (this is good) so we externalize it and forget to check the source, cross-verify, or check the date (this is less good).

- Ask the Internet for verification. There's a useful Discord server. Check: www.projectowl.one. They are an Open Source Intelligence community. You can post a piece of info on the Discord and have people try and verify it.

Remember to take a break from reading all of these dreadful news. Surely humans are not meant to process such a large amount of vivid violent imagery.

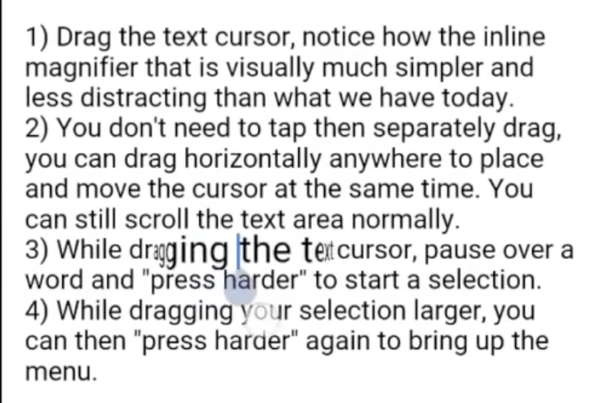

Eloquent is a New Paradigm for Mobile Text Editing

Editing text on mobile is cumbersome.

If people make a mistake, they would rather delete a word than attempt to edit it. This is why I was so interested in Eloquent's solution as it addresses the problem directly. Watch the intro video here.

It improves the current text editing experience in three ways:

- There is a permanently visible affordance (button) to indicate where the user can tap to move it. It is the dark, pale blue droplet below the cursor in the image above. The cursor instantly jumps to wherever the user taps on the block of text.

- The cursor and magnifier are visually unified to simplify targeting the right word or letter.

- You can select a word by dragging, then pausing, then pressing harder. No more double tapping, and fewer instances of the formatting menu popping out.

If an Apple engineer reads this blog, please consider trying some of these interactions.