Nvidia's CEO defends his moat as AI labs change how they improve their AI models

“Foundation model pretraining scaling is intact and it’s continuing,” said Huang on Wednesday. “As you know, this is an empirical law, not a fundamental physical law, but the evidence is that it continues to scale. What we’re learning, however, is that it’s not enough.”

That's also what I would say, if the growth of my business depended on people buying my chips, which are the gold standard for pre-training.

Source: TechCrunch

Chienne de vie

Chienne de vie. Il n’y a pas de saison pour se sentir comme un mégot écrasé entre les gros doigts poisseux du Hasard. Et pourtant. Aucun regard, aucun amour, aucune civilisation ne résiste aux immenses roues du Temps. Il aplatit tout Passé et forme un horizon laid sur lequel nos yeux se fixent malgré nous. Est-ce ça l’enfer ? Une plage longue et lisse faite de vide dans laquelle la seule chose à voir est ce laid horizon. Ça ne peut pas être ça. Il existe malgré tout des lueurs qui frémissent. Dans ces abris temporaires creusés par la lumière se trouve un répit qui accueille. Trouver les lueurs et y courir.

Mais c’est vrai, il n’y a pas de soleil caché derrière les nuages. C’est à nous de trouver l’eau dans ce désert même quand ces lueurs semblent être des mirages. Inscrire sur le sable de cette plage vide nos vœux avec ferveur, ce que l’on souhaite voir exister pendant cette chienne de vie. On peut faire beaucoup, on le doit certainement. Entendre la réalité de l’autre, l’épauler et le surprendre quand la tempête gronde. Cette chance que l’on crée pour autrui par notre présence ne garantit aucun changement, aucun succès. On échoue trop souvent. Mais c’est bien dans ces mouvements répétés, en tendant sa main encore et encore, que l’on trouve la force de regarder l’Absurde, pas comme un adversaire, mais comme une drôle d’étoile qui nous guide sans nous éclairer. Un compagnon indéniable qui prend souvent sans rendre. Oui, il reste beaucoup à faire pour marcher cette route sans se tourner vers la plage vide et lisse de l’enfer, ni vers l’horizon laid du Passé aplati par le Temps. Encore beaucoup !

Wittgenstein's word games, or how to communicate (a bit) better

Wittgenstein, the philosopher of language, may give us clues for better communication and self-understanding.

In ancient Greece, words like "justice" and "knowledge" were used without hesitation, conveyed through examples. There were no definitions proper. Socrates came along and asked, "What is justice? What is knowledge?" He thought words correspond to things. Examples capture only partial information about a word. This is his "name" theory of language.

Socrates sought definitions for all instances of a word. Wittgenstein, however, saw Socratic dialogues as a "frightful waste of time," proving nothing.

Wittgenstein proposed "family resemblances" between instances of a word's use, like traits shared among family members. Consider "game": board games, ball games, video games... no single commonality, but overlapping similarities and affinities. They are all "games". There might be a definition that encapsulate all but would need to be changed for any new "thing" that looks like a "game". Wittgenstein proposes to stop thinking... and to just look... for meaning of what is said.

A single word can form a family without one common essence. Seeking a single definition is nonsense. Definitions describe usage patterns! Not a word's true nature. Maybe this is why poets help us see new light on known words. And unlike Socrates proposed, word don't correspond to things.

Language can make us prey to unsound assumptions. How many misunderstood messages? Too many but it's just life. One solution is perspective: seeing words as tools for various uses/usage patterns, not labels attached to things. The meaning of "justice" depends on the activity at hand.

This applies to religion too. It is not about metaphysical claims, but a passionate commitment to living by a certain interpretation of life. Seen like this, religion resembles philosophy to some extent. Religious language expresses practical commitment, not factual/scientific belief. These language games are not necessarily in conflict.

Words are tools... we use to play "language games" in communication. Not by ill intent. But because words are complex and don't have a singular definition. Just as a court uses model cars to explain an accident, we paint mental pictures for others with our words

When a parent tells a scared child, "Don't worry everything is going to be fine," they aren't playing the Rational Prediction From Available Facts game, but rather the Words as an Instrument of Comfort and Security game. So is the colleague playing "Constructive Criticism" or "Office Politics"?

Failing to recognize the language game in front of us creates misunderstandings. It is harder than just "saying it". Even though everyone is better off when the talk is plain and straight. If your partner says, "You never help me. You're so unreliable," they may sound like they're playing the Stating the Facts game, but are playing the Seeking Reassurance game. Context is key.

Better communicators stay aware of identify language game being played. They can offer or ask for clarification of intent. They can stay flexible and not jump to conclusions based on singular words. They can accept ambiguity. Use meta-communication "I'm not sure how to say this but..."

What allowed Wittgenstein to adopt this radical view? A lifelong and overriding commitment to clarity and perspective as inherently valuable. Truth maybe matters less than clear sight - really seeing what's before us.

Again, don't think, look

Consequently, hosting a lavish banquet or ordering lobster is no longer a sufficient signifier of status; today, a sign of true wealth is the ability to forgo food entirely. Eating essentially betrays a person’s most basic human needs; in an era obsessed with ‘self-optimisation’, not eating suggests that a person is somehow ‘beyond’ needs and has achieved total mastery of their body with a heightened capacity for efficiency and focus.

What joy!

— Source

Mistral and culture

“The whole A.G.I. rhetoric is about creating God,” he said. “I don’t believe in God. I’m a strong atheist. So I don’t believe in A.G.I.”

A more imminent threat, he said, is the one posed by American A.I. giants to cultures around the globe.

“These models are producing content and shaping our cultural understanding of the world,” Mr. Mensch said. “And as it turns out, the values of France and the values of the United States differ in subtle but important ways.”

But this has been happening since the Second World War Mr. Mensch. And it's not stopping now, even though you realized it.

— NYT

Klarnas AI assistant, powered by @OpenAI, has in its first 4 weeks handled 2.3 m customer service chats and the data and insights are staggering: – Handles 2/3 rd of our customer service enquires – On par with humans on customer satisfaction – Higher accuracy leading to a 25% reduction in repeat inquiries – Customer resolves their errands in 2 min vs 11 min – Live 24/7 in over 23 markets, communicating in over 35 languages It performs the equivalent job of 700 full time agent

Oh yes, it’s happening. — Marginal Revolution

Amazon lets advertisers use generative AI to make product shots more lifelike

For advertisers without a graphic design or creative team, this is a quick solution to spruce up images that would otherwise be a bore

Complement this with auto-generated product descriptions, and Amazon might be one of the only Big Tech company making the most impactful “under the hood” AI improvements for their customers. That is, they are not making fancy bots or automatic PowerPoints and over-doing the “we're riding the AI wave” thing.

Also, to note:

Amazon says putting products in a lifestyle scene can lead to 40 percent higher click-through rates

How to Pour a Beer the Right Way

How do you pour a beer? You think you know the answer. You’re pouring the beer into a tilted glass, and minimizing the foam. According to Max Bakker, a Master Cicerone (or sommelier for beer), you’re getting it wrong. Above, he demonstrates the proper technique. Watch and learn.

The Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics

The Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics says that you can have a particle spinning clockwise and counterclockwise at the same time – until you look at it, at which point it definitely becomes one or the other. The theory claims that observing reality fundamentally changes it.

The Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics says that when you observe or interact with a problem in any way, you can be blamed for it. At the very least, you are to blame for not doing more. Even if you don’t make the problem worse, even if you make it slightly better, the ethical burden of the problem falls on you as soon as you observe it. In particular, if you interact with a problem and benefit from it, you are a complete monster. I don’t subscribe to this school of thought, but it seems pretty popular.

The Word Algorithm Originates in 9th Century Baghdad

The word algorithm comes from the name of a Persian mathematical genius, al-Khwarizmi, who dealt with mathematical sorcery in the 9th century. Although he did not invent algorithms in their contemporary sense i.e a finite sequence of rigorous instructions, he did inspire the Western world to use Arabic numerals instead of the clumsy Roman system. And he can be thanked for the word algebra.

It is when his works were translated into Latin and Italian that his name transformed into Algoritmi. And then his name entered the mainstream when it started to mean arithmetic in English.

It is striking to think that some people’s names became the semantic representation of an essential concept of science and technology. How often did that happen? — youtube.com

A Product Model to help PMs communicate clearly

I dream of a world where a Product Model can be generated from the organization of the backend files that respect the Domain-Driven Design (DDD) approach. That would quickly enable Product people to formalize a shared language from real code, and not spend hours philosophizing about why X should be named Y. Alas, this time has yet to come.

Indeed, one of the hard things to do in product development is to come up with a naming convention for your app that makes sense to everyone. Engineers, designers, and everyone else on the team need this shared language to talk about the product.

Another thing that is important for Product Managers is the ability to quickly conceptualize requirements for a feature or a product. Sometimes, user stories are too vague or incomplete.

Taking free inspiration from DDD, which states that in naming, the engineering logic must be as close as possible to the real-world, business logic, we can imagine the following model:

Domain Layer

This is where we name the entities and concepts that power the product. Domains are where the unique business logic is expressed. Say you are building an ecommerce app, you might have Cart, Accounts or Payments. If you're building an AI companion dating app, you might have Profile or Chat.

Infrastructure Layer

To me, this is where the backend orchestrates services that talk back and forth with the database. This is where I might refer to purely technical, non-visual elements such as a matching algorithm or a dedicated LLM logic.

Application Layer

This is the traditionally used layer when Product people think about products. This can capture interaction-based, user-centered flows that blend different objects from the Domain and Infrastructure layers, such as Sign Up or Add Item to Cart.

In short, because software applications are complex systems, thinking about the Application layer is not enough.

Product people should take into account the impact of a new feature in conceptual terms (Domains) and in technical, non-visual terms (Infrastructure).

Some Tips to Detect Fake News

Two things to keep in mind:

Remember the business model of media entities. Beneath the noble intention of sharing information, the business model of media companies is to maximize the number of people seeing ads on their properties, so they maximize traffic. How? Boring stuff doesn't drive traffic, but drama, and thus exaggeration, does.

Remember the goal of arguments, even online. A successful argument refutes the central thesis of the other party's argument. Beware of fallacies and biases like personal attacks (ad hominem), misrepresenting/exaggerating the opponent's argument to make it easier to attack (straw man fallacy), or saying that something is true because it's supported by an authority (appeal to authority). There are many more.

Without further ado, here are the tips:

- Check the source. A random Twitter/X account with 13 followers can share a post with 1M views. But it doesn't mean that the content is legit. Even accounts with a lot of followers are unreliable. One example is The Spectator Index (2.5M followers) which always exaggerates its claims for more views. Check the replies, check the origin of the information. Who shared it first? Yes, reputable sources are very hard to find. A heuristic I use is that if the content is sensationalistic and without context, there is a good chance that the “fact” is being exploited.

- Cross-check with other sources. If only one source shares the information, and you feel that they might not be a primary source, then exercise caution. One source is not enough to guarantee the validity of the information. Consider checking other sources.

- Check dates & times. A lot of people discard checking the date or time of content they share. Don't be like them! Check the date & time.

- Beware of emotional manipulation. Maybe I'm weird but my radar is triggered when the content shared is particularly dramatic (physical abuse, suffering children). Indeed, whenever we see suffering, our rational mind shuts off, and we are outraged (this is good) so we externalize it and forget to check the source, cross-verify, or check the date (this is less good).

- Ask the Internet for verification. There's a useful Discord server. Check: www.projectowl.one. They are an Open Source Intelligence community. You can post a piece of info on the Discord and have people try and verify it.

Remember to take a break from reading all of these dreadful news. Surely humans are not meant to process such a large amount of vivid violent imagery.

Eloquent is a New Paradigm for Mobile Text Editing

Editing text on mobile is cumbersome.

If people make a mistake, they would rather delete a word than attempt to edit it. This is why I was so interested in Eloquent's solution as it addresses the problem directly. Watch the intro video here.

It improves the current text editing experience in three ways:

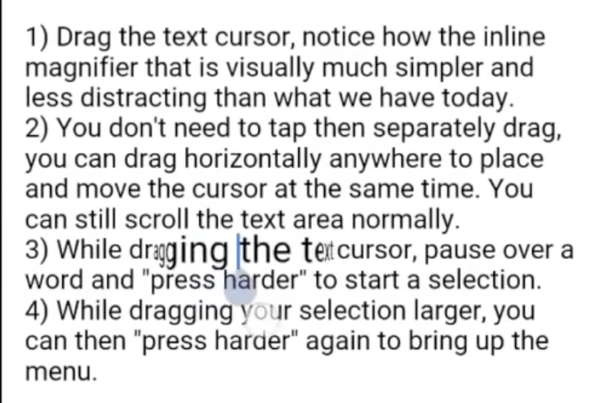

- There is a permanently visible affordance (button) to indicate where the user can tap to move it. It is the dark, pale blue droplet below the cursor in the image above. The cursor instantly jumps to wherever the user taps on the block of text.

- The cursor and magnifier are visually unified to simplify targeting the right word or letter.

- You can select a word by dragging, then pausing, then pressing harder. No more double tapping, and fewer instances of the formatting menu popping out.

If an Apple engineer reads this blog, please consider trying some of these interactions.

The CIA Read Allies Encrypted Communications — For Decades

In a surprising, ahem, move, the CIA owned the one company that numerous countries trusted for their cryptography needs:

For more than half a century, governments all over the world trusted a single company to keep the communications of their spies, soldiers and diplomats secret.

The company, Crypto AG, got its first break with a contract to build code-making machines for U.S. troops during World War II. Flush with cash, it became a dominant maker of encryption devices for decades, navigating waves of technology from mechanical gears to electronic circuits and, finally, silicon chips and software.

But what none of its customers ever knew was that Crypto AG was secretly owned by the CIA in a highly classified partnership with West German intelligence. These spy agencies rigged the company’s devices so they could easily break the codes that countries used to send encrypted messages.

Read more here.

Anne L'Huilier, Pierre Agostini, and Feren Krausz won the 2023 Physics Nobel Prize. They developed “attoseconds”, extremely short pulses of light where one attosecond is one billionth of a billionth of a second.

This allowed them to study the incredibly fast movements of electrons within atoms and molecules in real time. Before, it was impossible to observe such rapid movements because of their fleeting nature.

We now have a way to investigate the fundamental behaviors of electrons, which can enable a variety of technological advancements such as faster electronic devices and inroads in chemistry and biology.

Two further fun facts: Anne L'Huilier started working on this in the 1980s and got back to the amphitheater to continue her class after she got a call informing her she had won. Indeed, her greatest gift to humanity is her teaching.

Why We Like Bitter Foods In The 21st Century

Why is it that humans seem to increasingly enjoy bitter foods?

Examples include IPA beer, Aperol (sales have increased x5 from 2010 to 2022), or 100% cacao chocolate.

One theory is that people have been acribing better health outcomes to things that are hard to like, like bitter foods, in opposition to sweet stuff. This is because sugar is now universally considered as something bad for your health, and is very easy thing to eat.

Another possibility is that we turn to less palatable foods because they are perceived to be more natural. Nature yields unsavory stuff, right?

Of course, the venerable mango is a compelling counter.

Beautiful Lidar images of rivers. Courtesy of Dan Coecarto.

Why Apple Will Not Release a Google-like Search Engine

It is reasoned that comments from Apple SVP of Services Eddy Cue saying Google’s search is the best and that Apple has no incentive to make its own are probably true, but could also be a measure to try and protect Google from government enforcement.

A rumor has it that Apple is developing its own search engine to compete with Google. This is true, as Apple must create some crawling/ranking software for Siri, Spotlight and such. However, I do not believe they are going to release a proper search engine. The reason for this rumor could be related to the anti-trust lawsuit against Google, and Apple is defending them. The incentives for the deal are too good for Apple, they are getting $15B a year for almost 0 effort.

On Voice in AI Companions

Those of us who are blessed to have many close friends and family members in our life may look down on tools like this, experiencing what they offer as a cloying simulacrum of the human experience. But I imagine it might feel different for those who are lonely, isolated, or on the margins. On an early episode of Hard Fork, a trans teenager sent in a voice memo to tell us about using ChatGPT to get daily affirmations about identity issues. The power of giving what were then text messages a warm and kindly voice, I think, should not be underestimated.

Good insight from Casey Newton.

I saw a tweet about a game where you guess Paris metro stations this morning but can’t find it anymore. I think it’s someone’s side project?